Make your 2X MATCHED gift today!

This week only: Every $1 will be matched with $2 to enable women worldwide.

This week only: Every $1 will be matched with $2 to enable women worldwide.

Posted on 03/01/2023

Big thanks to Ronald Lim, with Grameen Foundation-Philippines, for photo-documenting, translating and answering my innumerable questions during my visit. All photos with me in them are credited to Ronald and Grameen.

About 40 years ago, a group of neighbors banded together to fight the high prices of the only local shop. The residents lived in Mangloy, a village in the municipality of Laak, in the province of Davao de Oro on the large southern Philippine Island of Mindanao. The cooperative they formed in the 1980s in Mangloy now serves about 4000 members throughout the municipality and is called Laak Multipurpose Cooperative or LAMPCO.

They still provide household necessities like rice and oil, plus serve their farmer-members in the vital role of “middlemen” traders by purchasing and selling dried coconut (called copra), unhusked rice (pasay), and dried cacao beans. Besides the three retail shops, commodity trade and primary processing, the cooperative serves members with affordable loans for household emergencies, home improvement loans and farming needs.

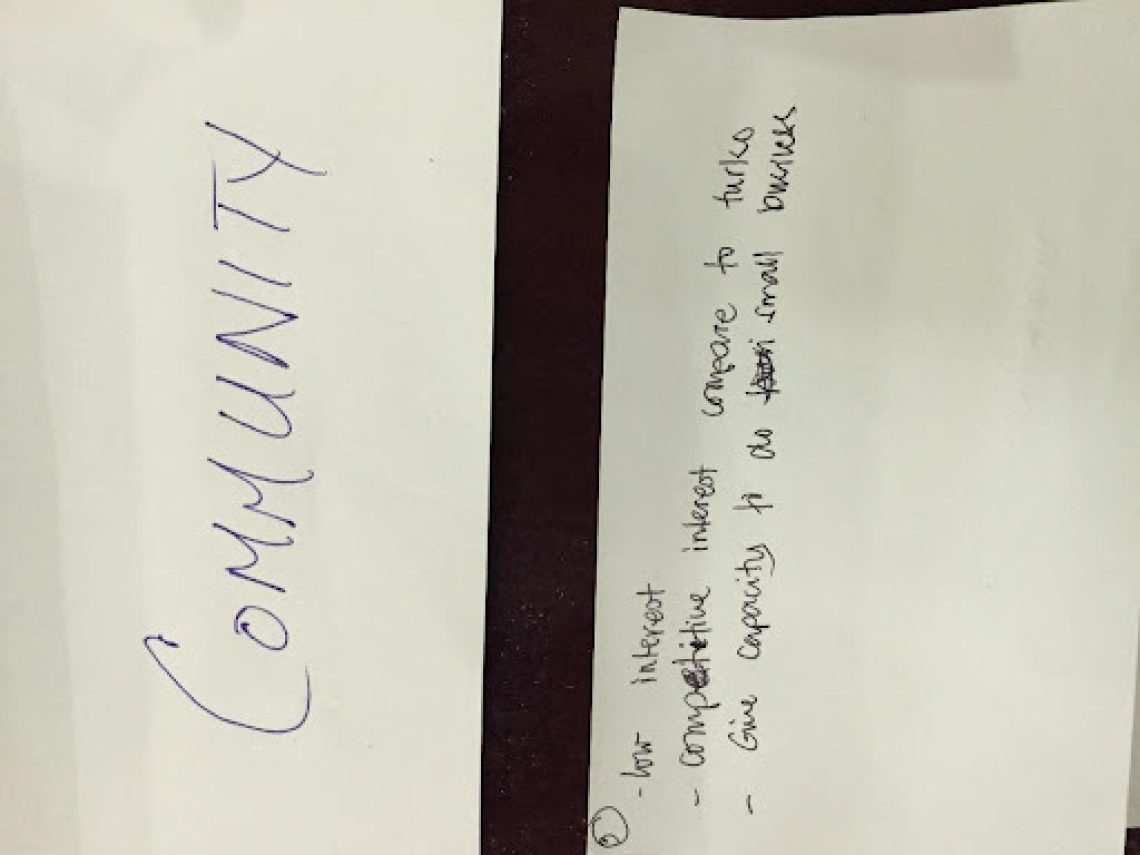

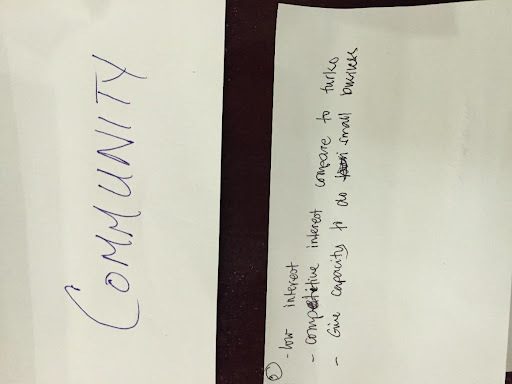

Similar to the transparency offered in their commodity purchasing and processing and low-priced household goods, loans are offered at bargain rates, typically between 2 to 3.5% interest per year. Like many lenders during the pandemic, LAMPCO experienced a spike in loans that were at risk of not being repaid. Their total lending portfolio (what a group of loans is called) had repayment rates that put the risk of non-repayment (known as portfolio-at-risk, or PAR) at 72%. In other words, of the total value of the loans, nearly three-quarters of the total might not be repaid as expected.

With the help of Grameen Foundation and the improving financial conditions after the initial COVID lockdowns, LAMPCOs’ PAR improved to 55%. Part of this was facilitated by consulting advice from a microfinance institution (MFI) based in Cambodia, who coached LAMPCO through improvements to their lending practices. Subsequently, volunteers through Grameen Foundation’s Bankers-without-Borders Program, funded through a grant from USAID’s Farmer-to-Farmer initiative, created and simplified a credit scorecard.

This is where my small part in the story picks up: I consulted with LAMPCO in January 2023 to ensure the smooth uptake of the scorecard and provide feedback on potential ways to improve the scoring process and integration. Two previous volunteers, Cheri St. John and Flora Sun, both retired banking gurus who were instrumental in creating more responsible lending operations in the USA, created a basic scorecard LAMPCO loan officers could use to rank borrowers based on characteristics like their income, loan repayment history, savings rate, etc. The loan officers, branch managers, general manager and board members learned (via Zoom, of course!) how to use the Excel-based scorecard in July 2022 and have been scoring loans since then.

When I arrived in mid-January 2023, the general manager, Edesa Morante, and the Grameen Foundation officer, Ronald Lim, along with the board of directors, oriented me to the LAMPCO operations. We visited the branch managers and loan officers of each of the six LAMPCO branches with lending operations: Aguinaldo, Kidawa, Kilagding, Laak, Mangloy, and Sawata. We discussed how they were using the scorecard and recording the data; their likes and dislikes of the process; and made sure each branch had the Excel template stored and available on the computers. We also enjoyed delicious afternoon breaks, called merienda, with my favorites: biko (sticky rice and coconut treats) and buko juice (the water from young coconuts, usually mixed with coconut meat and condensed milk).

The branch loan officers and LAMPCO’s lead accountant, Cecil, graciously shared the scorecard and loan data with me, which I eagerly condensed and put through some basic filters and formulas to see what the still-new datasets could tell us. Promisingly, the repayments seem to be improving, and the loan officers had no dislikes of the scorecard or the process. Each appreciated the easy to understand interpretation of borrower risk. They felt the process helps them better serve their borrowers by guiding them to offer appropriately sized loans and repayment schedules, decreasing the risk for both the borrower and LAMPCO.

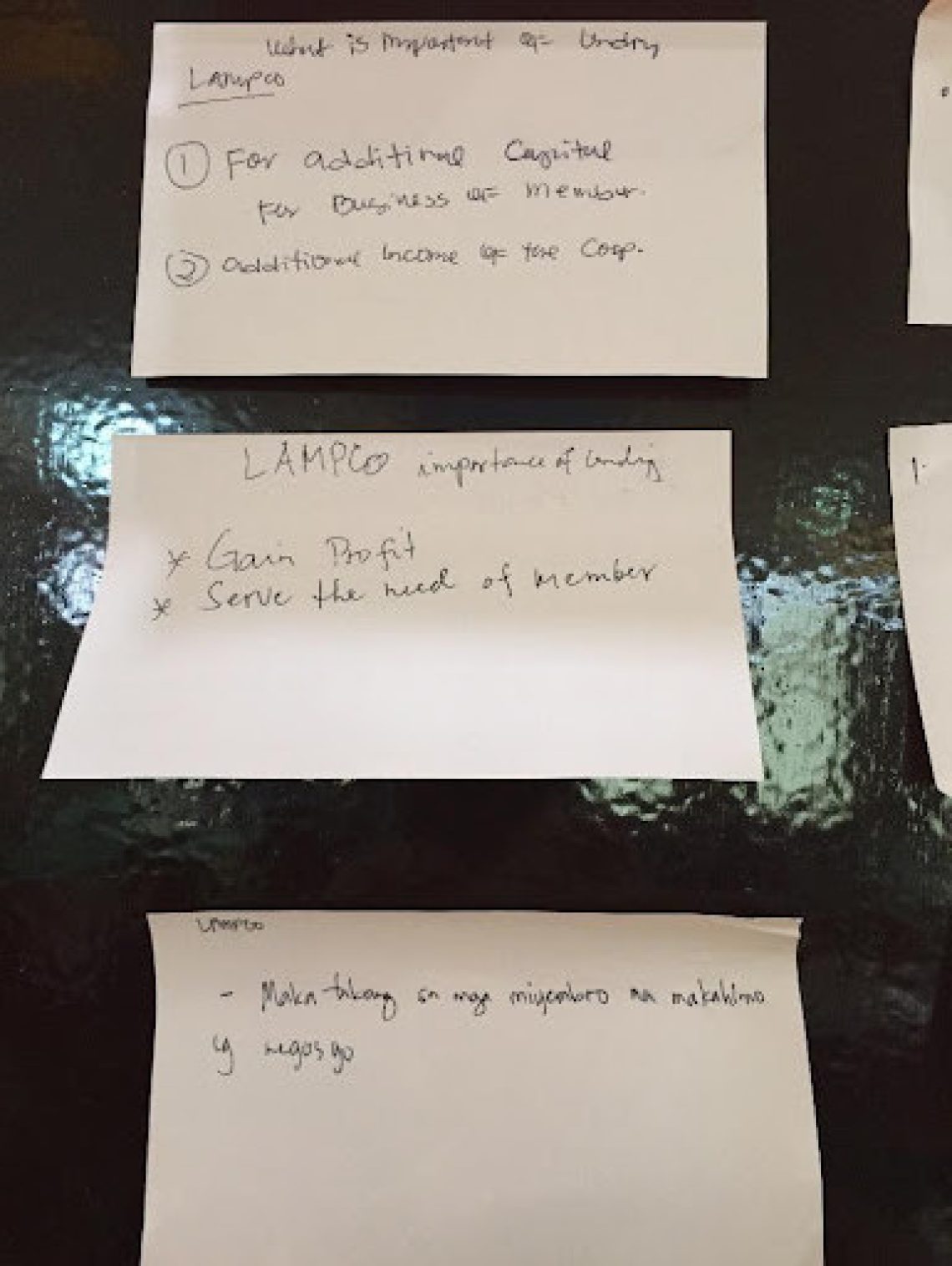

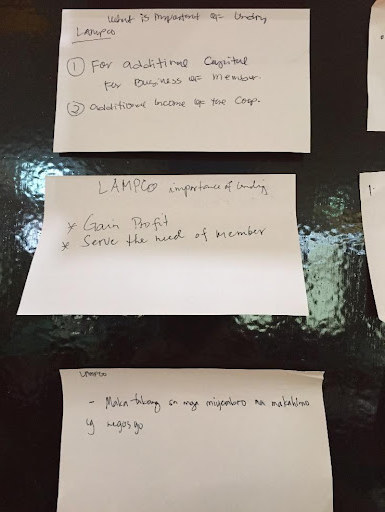

After these valuable interviews and with the infinite patience of Ma’am Edesa and Sir Ronald (ma’am and sir are frequently used terms of respect in the Philippines) as they answered my limitless questions, we were able to draw some conclusions and determine some useful topics for the workshop I led on my last day. With the enthusiastic participation of the head office staff, loan officers and branch managers, we spent about six hours discussing the implications of the diligently collected scorecard data; learning the basics of good data collection and analysis; planning to manage the lending and repayment processes for success; and immediate next steps.

Consulting with the LAMPCO team, Ronald and the previous volunteers, Cheri and Flora, I made recommendations for LAMPCO to continue using the scorecard and conducting basic data analysis; and recruit additional volunteers to analyze PAR and the scoring summaries once additional three to six months of data has been collected.

I didn’t have too much of an idea of Filippino culture before I left for my trip, but I was familiar with all the inherent geologic and weather dangers they routinely face. Acknowledging the inherent risks of generalizing an entire culture, my overall impressions is that although there may be many subtleties between regions, the overall spirit is one of resilience. Pessimism is so easy, but that is not their choice. Filippinos take pride in rising up together after vicious typhoons and not admitting defeat against everyday calamities that would likely knock me down pretty hard. So I have confidence that LAMPCO will continue to learn and adapt to provide the best service to their members for years to come.

The folks at LAMPCO wanted to make sure I saw more than just their lovely agrarian municipality, so we took a Sunday trip to Hinatuan (pronounced hen-a-TOO-an) to see the Enchanted River. And enchanted it is! This natural phenomenon is a salty, crystal clear river that flows about a kilometer before reaching the sea. The salinity and great depth--over 25 meter of the most azure-blue water at the beginning--are due to an intricate cave system. We swam in the cool water for a while, watched the fish feeding ceremony, and then took a boat island-hopping in the bay. A small boat with outriggers, the same kind of vessels used for fishing, ferried us to four nearby islands where we ate a delicious lunch of boiled crab, squid, tuna, and rice; jumped off high dives; and looked for sea turtles in the healthy seagrass beds. On our way home over the lush and verdant mountain passes, we stopped to see the flooded falls of Tinuy-An followed by dinner at the same place we had breakfast about twelve hours before, a roadside kambingan, a place to eat roasted goat and lechon manok (roasted local chicken).

Speaking of food, another part of Filippino culture I didn’t anticipate was just how delicious the food would be. From the freshest and most delicious fruits like saguing (bananas), durian, and marang to the abundant rice, isda (fish), and kambing (goat), I gained at least two very delicious, worth-every-bite pounds over my three weeks. Breakfast might be eggs, sausage and serving of rice or my personal favorite, sardines or other small fried fish with eggs and rice. Lunch may be chop suey vegetables and kinilaw, a type of vinegar dish that could feature fish or pork, and supper usually was a large affair, potentially with a soup like tinola (vegetables and seafood flavor) or bulalo (beef soup), liempo (crispy-roast pork belly), and roasted hito (catfish). My favorite dish was pinakbet, a veggie-heavy dish of green beans, kobocha or similar hard squash, bits of pork belly and usually some shrimp.

Finally, but perhaps most importantly to my memories, is part of the culture I observed that is somewhat hard to explain in words. Essentially, people interact with each other more than they do in my part of the world, something I’ve experienced in other places but might not have appreciated. Dozens of times a day, there are mundane but pleasant interactions, each one building on the other until at the end of the day, you’ve accumulated a day full of smiles and laughs, even when much of the day might be spent talking about not necessarily amusing things like low loan repayment rates.

Starting the day with a jog around the town where our hotel was, Tagum City, I’d see dozens of folks on the streets. From the street sweeper ladies with their whisk brooms, to uniformed and pig-tailed schoolgirls, each morning about a dozen folks would smile and greet me with a pleasant “Good morning, ma’am!”. Driving with Kyong-Kyong, the LAMPCO driver, and Ronald to Laak from Tagum each day, we witnessed the small moments of everyday life – kids laughing and playing basketball on the courts of the barangays we passed through, shop ladies on the side of the road visiting with customers, and families of three or four hugging each other contently on their scooter. Each evening, I’d wander through the hundred or more stalls set up on the streets of the small-ish city of Tagum, selling everything from street food to shoes to cell phones. Teenagers with their boyfriends, boys skateboarding in the local park, and adults sharing stories over fried food and endless skewers for bbq’ing filled the main square and the surrounding streets. Psychologists might call my observations and interactions “positive weak ties”. Whatever you call it, despite the fact that I’m only about 50% extrovert, these small moments added up to make my days happy, and my time spent sifting data in Excel flew past.

My time in the Philippines provided an extraordinarily fulfilling experience working with LAMPCO and immersing in the local culture. I couldn’t recommend volunteering with Grameen Foundation in the Philippines more highly to anyone who is inclined and has skills in agronomy, coconut growing and processing, chocolate-making or finance.